Gracefully Chic: The Fashions of Philip Hulitar New exhibit opening July 27th

Stony Brook, NY – June 28, 2019

Stony Brook, NY – June 28, 2019

From July 27th to October 20th the Long Island Museum will proudly present the exhibit, Gracefully Chic: The Fashions of Phillip Hulitar. This will be the first major retrospective exhibition to explore the work and lasting influence of mid-20th century designer Philip Hulitar (1905-1992). In the rapidly-changing world of postwar American couture, Hulitar became known for his distinctively tailored and elegantly decorated cocktail dresses and evening gowns. Launching his label in 1949 after 18 years of success as one of Bergdorf Goodman’s chief designers and head of its women’s dress division, Hulitar quickly earned critical acclaim and a fervent following in New York and Long Island society. “The star of a gifted designer has risen recently on the fashion horizon,” one contemporary journalist stated, shortly after his business opened.

Hulitar’s consistent success in each new runway season throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, including a spectacular showing at the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels, gave him a discerning audience for his precise interpretations of glamour. He converged an Old World upbringing and sensibility – his father was a Hungarian diplomat and his mother came from Italian nobility – with a thoroughly modernized American one, arriving and building his career in Great Depression New York in his mid-20s. Marrying the charming and beautiful Mary Perry Gerstenberg (of New York and North Shore Long Island) in 1951, Hulitar built a life around his work, extensive travels, and love of art. The Hulitars were also active and extraordinarily generous members of their communities in Palm Beach and Long Island.

“His designs really evoke an era,” says the exhibition’s curator, Deputy Director Joshua Ruff. “His dresses were sold in department stores and high-end boutiques all across the country, from Boston to Seattle, and a number of famous actresses—Rosemary Clooney, Jane Fonda, Lee Meriwether, Patty Duke, and Joan Fontaine—all wore his clothing.”

In our interactive dressing room, set up to look like an early 1960s department store, the museum invites visitors to try on a Hulitar replica. Dresses of various sizes — with Velcro panels to make them easy to slide over regular clothes — have been reproduced from an original Hulitar pattern. Visitors can try on the dresses and take selfies wearing Hulitar creations.

The Long Island Museum is proud to be the first museum to fully explore Hulitar’s influence and work. Gracefully Chic will utilize loans of the designer’s drawings, apparel, and dresses from the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; the Philadelphia Museum of Art; the Museum of the City of New York; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and a variety of other public and private sources. It is only appropriate that the Long Island Museum – home of The Mary & Philip Hulitar Textile Collection – should be the place to mount this important exhibition.

About the Long Island Museum:

Located at 1200 Route 25A in Stony Brook, the Long Island Museum is a Smithsonian Affiliate dedicated to enhancing the lives of adults and children with an understanding of Long Island’s rich history and diverse cultures. Regular museum hours are Thursday through Saturday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Sunday from noon to 5 p.m. Admission is $10 for adults, $7 for seniors, and $5 for students 6 -17 and college students with I.D. Children under six are admitted for free. For more information visit longislandmuseum.org.

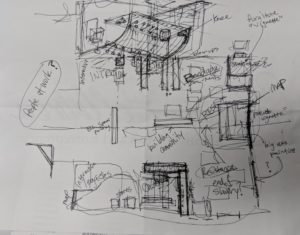

It’s January 31, 2019; two weeks and one day until opening day of one of the most important exhibitions the Long Island Museum has ever done and here is where we are:

It’s January 31, 2019; two weeks and one day until opening day of one of the most important exhibitions the Long Island Museum has ever done and here is where we are:

So after about 18 months of planning, drawing, constructing and assembling (over 200 man hours in the week leading up to opening day alone) our curatorial team, consisting of exactly five people, along with the help of seven consultants and a maintenance staff of three, completed the exhibition and had it ready for opening day.

So after about 18 months of planning, drawing, constructing and assembling (over 200 man hours in the week leading up to opening day alone) our curatorial team, consisting of exactly five people, along with the help of seven consultants and a maintenance staff of three, completed the exhibition and had it ready for opening day.