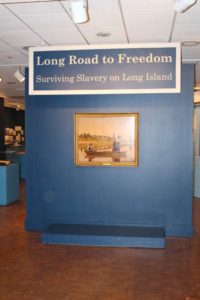

Building an Exhibition

Long Road to Freedom: Surviving Slavery on Long Island

It’s January 31, 2019; two weeks and one day until opening day of one of the most important exhibitions the Long Island Museum has ever done and here is where we are:

It’s January 31, 2019; two weeks and one day until opening day of one of the most important exhibitions the Long Island Museum has ever done and here is where we are:

How, you might wonder, does this pile of hardware and paint splotches become a world-class, impactful exhibition on such a major subject on a limited budget? To answer that question, we need to go back to the fall of 2017, when our curatorial staff began discussing an exhibition examining slavery on Long Island – a topic that had come up more than once in various meetings over the past couple years.

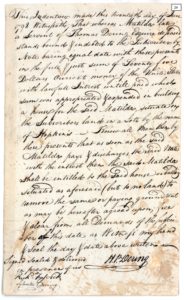

Curator Jonathan Olly, who joined the museum staff in 2016 as Assistant Curator, was assigned the task of organizing the show (that’s insider lingo for the more formal term EXHIBITION). A challenging task given, according to him, “documents are the most common type of surviving artifacts from the period of slavery on Long Island. There are no known items of clothing, photographs, shackles, paintings, or other objects that either depict enslaved African Americans on Long Island or were owned by them.”

Fortunately, he had a committee of advisors to consult with on some of the research and findings, who helped sift through the information to tell the story about slavery.

But how does one go about organizing an exhibition from documents? I should explain that the documents we’re talking about are most commonly letters, contracts and bills of sale…for human beings. Imagine trying to tell the world about your beloved grandmother with nothing but a birth certificate to prove she lived.

So you can see the challenge here.

Jonathan explains, “One way is to show objects that are products of the slave trade, such as the mahogany furniture with which wealthy Long Islanders furnished their homes. The wood used to make this furniture was harvested by enslaved labor.”

“Additionally, many of these wealthy Long Island households had enslaved servants, who would have moved, cleaned, repaired or otherwise used this furniture. Archaeological material likewise provided examples of things that enslaved people on Long Island likely handled.”

So at this point, I’m sure you’re wondering, just where does one find these archeological objects? Reportedly, 49 different organizations and individuals contributed items to the Long Road to Freedom exhibition. These included historical societies, libraries, other museums and individual lenders. Jonathan says he knew where to look for particular items partly by word of mouth. When talking to one museum or collector about an object, you learn where to go for the next object, and the next and so on until you have enough substance to start connecting the dots.

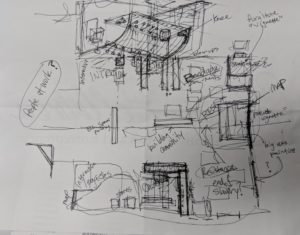

Here’s where it’s important to talk about the exhibition designer. Joe Esser, Exhibition Designer and Facilities Manager wears a lot of hats. In addition to his many other non-exhibition related responsibilities, he’s the guy who takes all those documents, objects and paintings you heard tell of, and visualizes where they go and how they should look in the gallery. Then he draws the whole gallery out on paper (or in a computer program) so he can show Jonathan and make adjustments as needed. Once they get a good idea of what goes where, the installation can begin.

Walls have to be painted, pedestals have to be built and vignettes have to be constructed. Yes, vignettes; those three dimensional sections of the exhibition that draw you in and illustrate exactly what those documents were talking about. For example, in his research Jonathan discovered a diagram of a slave ship’s hull that shows how enslaved Africans were carried to maximize space. But when I read about people being stacked and shackled in layers, it’s a little difficult to draw the picture in my mind. Sure, I saw Roots – the landmark 1977 miniseries about one family’s experience in slavery – but that was television. Surely that wasn’t how it really was.

Wrong. It really was. And it was awful. Yet it’s one of the most powerful sections of the exhibition because there it is in three dimensions, illustrating the conditions people were forced to endure. In addition, the exhibition features paintings, documents, videos and photographs all in one gallery that measures about 2800 square feet.

So after about 18 months of planning, drawing, constructing and assembling (over 200 man hours in the week leading up to opening day alone) our curatorial team, consisting of exactly five people, along with the help of seven consultants and a maintenance staff of three, completed the exhibition and had it ready for opening day.

So after about 18 months of planning, drawing, constructing and assembling (over 200 man hours in the week leading up to opening day alone) our curatorial team, consisting of exactly five people, along with the help of seven consultants and a maintenance staff of three, completed the exhibition and had it ready for opening day.

The final result is an exploration of two centuries of slavery and the subsequent growth of free communities of color on Long Island in the 19th century. If you haven’t seen Long Road to Freedom, you need to. The show runs through May 27 and is open Thursday through Saturday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Sunday from noon to 5 p.m.